On his 100th birthday

My grandfather Leo Reitzug, had been waiting for this moment a long time. Years, even. Tightly grasping his pipe, repeatedly feeding it more tobacco fished from his vest pocket, the usually placid Leo puffed and paced purposefully outside the room with the closed door. Intermittent noises escaped from the room. Inside, Mitze, his wife of nine and a half months, was giving birth to their first child.

A series of final triumphant yells was followed by the familiar screams of a baby. It was the first of many times mother and son raised voices in each other’s company. As with many subsequent full-throated decibel events that often penetrated adjoining rooms, Leo, a peacemaker by nature, inhaled audibly, clutched his pipe with his right hand, stroked his chin with the left, and tried to look calm.

Minutes later, allowed into the inner sanctum, admiring the newest resident of Mehlsack, he announced the boy would be named Nikolaus. Familiar with his grief of his last eight years, family members understood this was in honor of Leo’s brother Nikolaus who perished in the defense of the Kaiser and the Vaterland during the Great War.

Growing up in Allenstein, East Prussia’s second city, a mere 50 miles from the border with Russia, burly 21-year-old Leo and feisty brother Felix, had quickly signed up to defend their beloved Heimat when Russia invaded in July 1914. Feeling no less patriotic, 16-year-old Nikolaus, known by everyone as Klaus’che in the affectionate East Prussian way, soon joined the Kaiser’s army as well. It was over the objections of his mother Marie.

His father Gustav, an elite Black Husar in Bismarck’s German Army of the 1880’s, supported the decision. And Leo assured Marie he would look after the boy. Anxiously Gustav prayed God would bring all three sons home safely. Young Nikolaus, named after Gustav’s father, and the grandfather neither of them ever knew, was the apple of Gustav’s eye. “If anything happened to Klaus’che, …,” He could not finish the thought. But it haunted him constantly.

In November of that year, the ubiquitous Royal Eilpost letter arrived at the Reitzug home at Liebstädter Straße 23 in Allenstein bearing the awful news. “Our Kaiser has lost a brave warrior,” it began, as it always did. Close to two million of these letters would be delivered over the next four years.

He was buried in a joint Russian-German military cemetery in the Masurian Lakes region of East Prussia.

The loss of Klaus’che, shattered Gustav.

Having also lost his second-oldest daughter Elisabeth in childbirth that year – she was named after his mother who similarly died while giving birth – he became increasingly despondent. Orphaned early, ridiculed often about the events surrounding his own birth, he had lost his childhood prematurely. And now his adult life was losing its meaning as well. Unable to cope, he soon wound up spending the last few weeks of his life in the mental institution by the lake, just down the street from where all six of his children had been born.

Equally devastated was Leo, heaping copious blame on himself for allowing his baby brother to join the war. But now, eight years later, with this fourth Nikolaus born to the Reitzug clan, he was hopeful.

The first two Nikolaus’s had spelled their last name Reicuch, no doubt in deference to the language and influence of the region’s Polish-Lithuanian sovereignty of the 17th and 18th centuries. The 19th century brought back German rule and hope to East Prussia. Tragically, it also brought the wars of the 20th century, their devastation and loss of lives, and ultimately, the loss of homes and the sweet, God-fearing East Prussian way of life.

Chubby Nikolaus thrived as a baby in Mehlsack, near family, friends, and familiarity. By 1925 Leo and Mitze had moved the family to the Neu-Kölln area of Berlin. There they welcomed a second son, Heinrich, known as Heinz.

For the next 83 years, moving between Berlin, Osnabrück in West Germany, Mehlsack, and finally Fort Wayne, Indiana, in the US, Nikolaus would always see Mehlsack as his home and speak fondly and nostalgically of his time there.

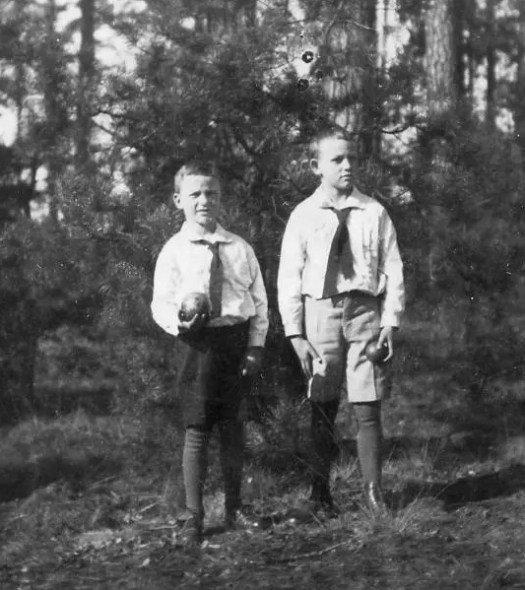

Growing up in Berlin Klaus and Heinz were best friends. Cousin Erika also lived in Berlin and the families enjoyed outings, picnics, and First Communions together.

But the fullness of life was not realized until the family moved back to Mehlsack. The idyllic Walschtal with its river and forests, the open East Prussian fields, Opa Anhuth’s big house, the established Catholicism of that region of East Prussia known as the Ermland, all contributed to the small town atmosphere that captured Klaus’s heart. Grandfather Hermann Anhuth would take him on walks through his fields and speak to him about what it meant to be a man of integrity. Lessons for life, later learned by his sons as well.

Automobiles, Fiat and Opel, were the family business. They lived in the house above the dealership across from the railroad station. The building did not survive World War II; a children’s playground occupies the site now.

The train station was conveniently located to take Klaus and Heinz to St. Adalbert School seven miles outside of town. Many days in 7th grade, the freedom of riding unaccompanied on a train was too much temptation for Klaus. His truancy caused him to have to repeat the grade, a matter seldom discussed. In fact, I did not hear about it until after he had had the ultimate graduation – to heaven, where such embarrassments no longer matter.

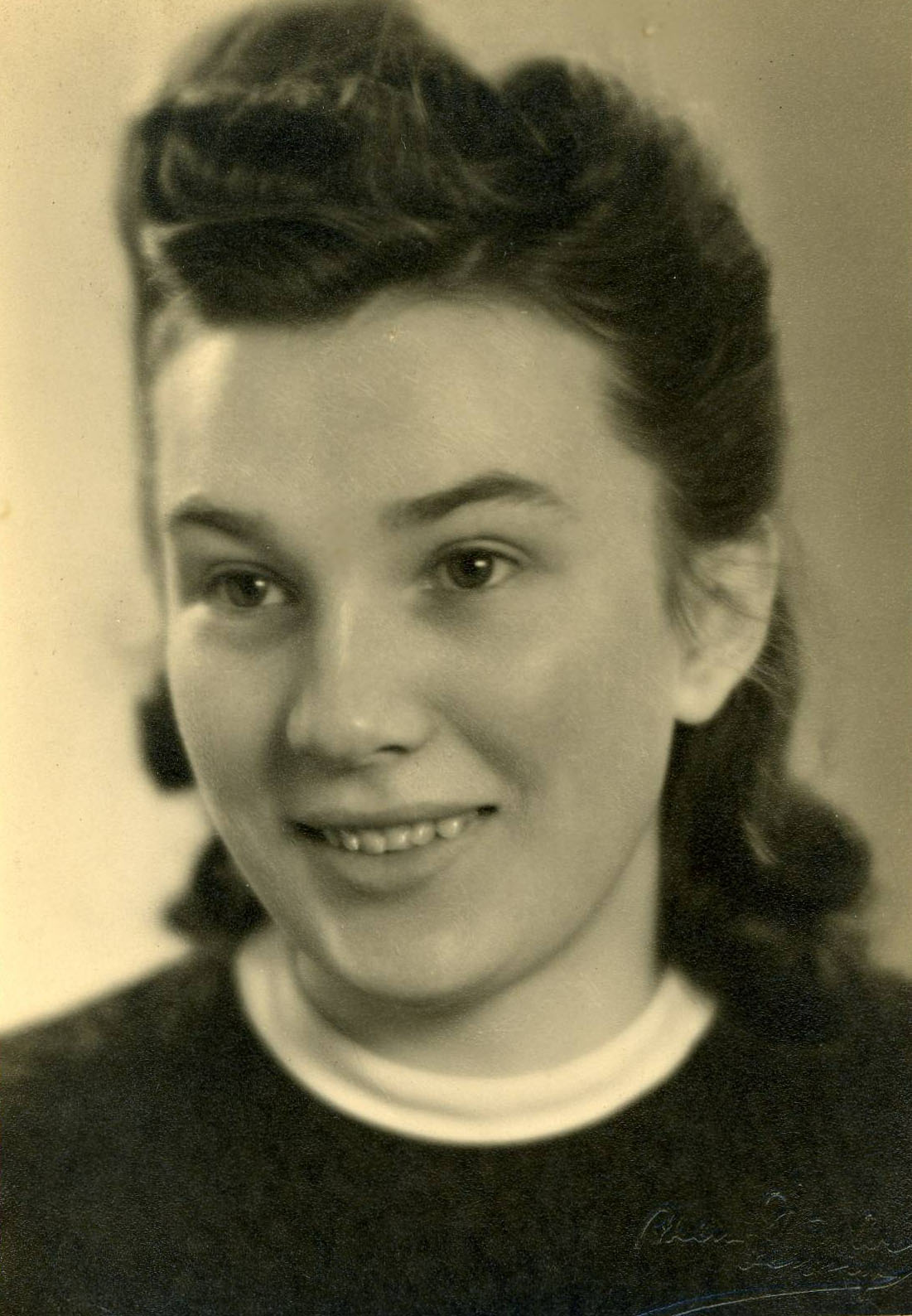

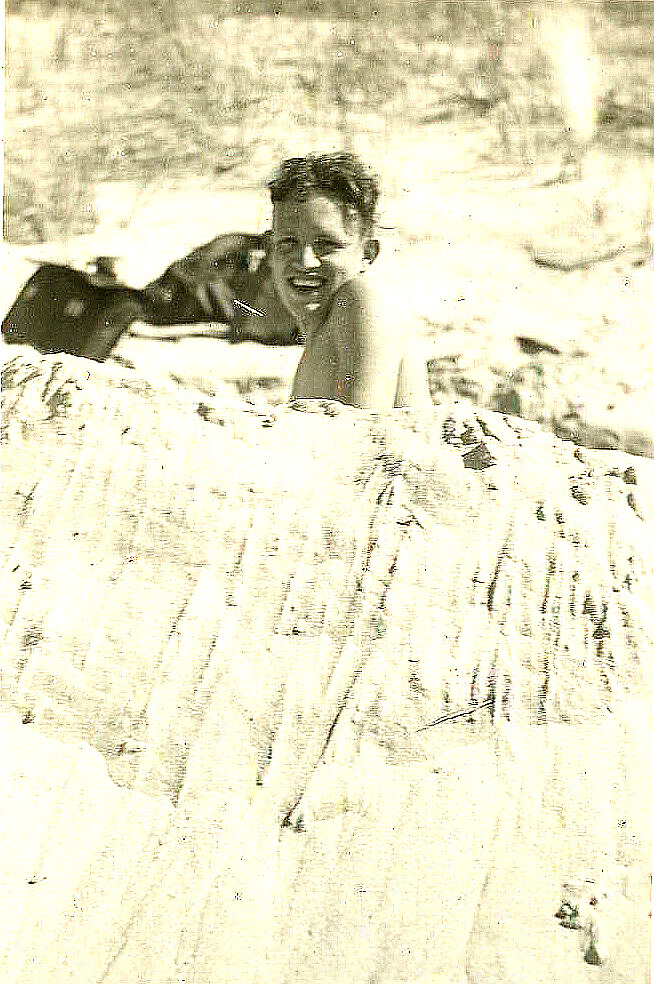

By the time Klaus was 14 he had met the love of his life, Elisabeth Klaffke. She and Grandpa Anhuth were the big influences in his life, and both lived in Mehlsack. Upon graduation, with Klaus joining the Luftwaffe, their courtship developed in earnest, in the Walschtal, in the company of both families joining together, and even an unchaperoned trip to the dunes of the Kuronian spit.

But the war took its toll.

Klaus was sent to the eastern front, to witness and inflict violence, to be seared by the daily life and death experiences of 202 combat missions. As he became older his naturally assertive nature came to resemble Post-Traumatic-Stress more and more. The wounds and the deeds of a savage war festered inside his heart and threatened at times to extinguish his tender side.

The smiling, laughing young man, the life of any gathering, had turned into a serious, sometimes cranky war veteran. It was not until the last year of his life when he confessed his deepest, dark secrets that he was set free of the ghosts of war.

His brother Heinz, after serving in a flak tower in Berlin for most of the war, was sent with the under-trained and under-equipped Volkssturm to stop the Russian advance on Berlin in April 1945. Leo, his father, then in his fifties, and never in the best of shape, was likewise sent.

In the words of Leo, repeated often, “I walked with Heinz as far as I could.” Knowing what fate awaited 19-year-old Heinz, and suffering from survivor guilt, Leo was tormented by this memory for the last 10 years of his life.

When I was born seven months after the war ended. It took very little persuading by Leo for my parents to name me Heinrich, in memory of the brother and son who did not return from the war.

Leo poured himself into my life, being the model of a grandfather. He even called me Heinz, the only one who did. As a child I was aware that I was replacing the son he had lost.

The war had been hard for Leo’s family in another way. He and his only surviving brother had a severe falling out over Felix joining the Nazi Party, imposing a 15-year silence on their relationship. He had joined the Party early on, a point of huge contention in the devoutly Catholic family. He became part of Organisation Todt, an engineering division which used slave labor to build concentration camps. Less than a year before Leo died of a heart attack they spoke for the first time since before the war, and they reconciled.

With the war hopelessly lost, Nikolaus was given permission in January 1945 to go home to marry his sweetheart in the parish church in Mehlsack.

Before he could return to his unit, the Russian advance had cut off their means of escape, necessitating a harrowing 11 km journey across a frozen estuary in a blizzard. Miraculously, the troop transport Klaus had been volunteered to lead across the ice made it to land safely, and eventually to Gdansk, with both him and Elisabeth unharmed.

Close to two million East Prussians fled that way. Many succumbed on the flight to safety. The ones who made it to West Germany found there was no housing for them, not enough food, and no welcome.

I climbed up to the balcony of a church steeple and saw where they embarked onto the ice and crossed to the distant spit of land.

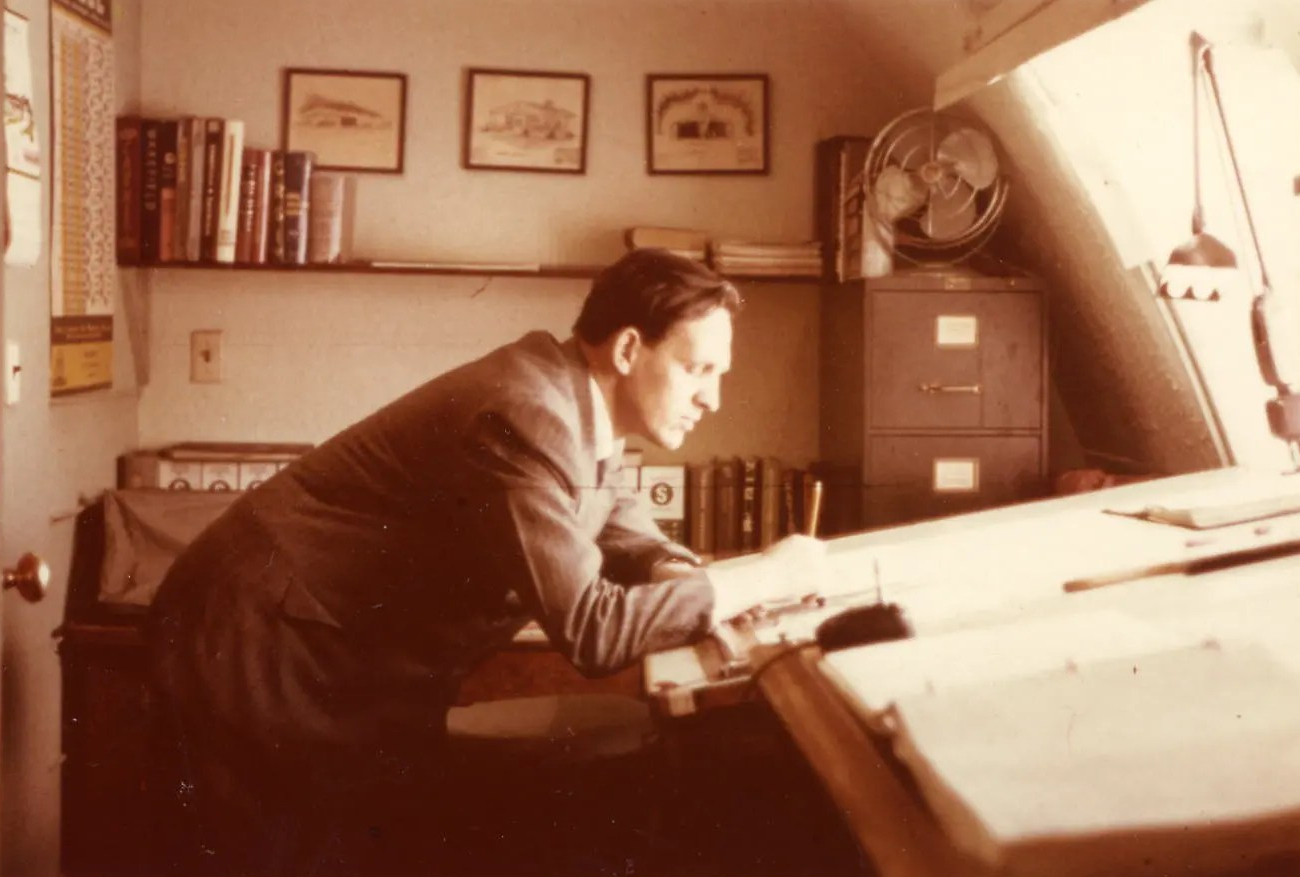

With his father’s help Nikolaus was accepted into architecture school. Leo also renewed connections in the car industry in Osnabrueck and landed a job on the design team for the Karmann-Ghia. He, Klaus, and Lisel were housed in a two-room apartment with a shared toilet a half floor down. I was born there.

By the time Mitze was released from the Displaced Persons camp in Denmark in 1949, we had larger accommodations. And it was clear that East Prussia now belonged to Poland and a return was unlikely. This hit my father Nikolaus particularly hard. For the rest of his life he spoke of having lost his Heimat. It had clearly left a hole in his heart. He grieved for the old ways, the lovely country, and the land of his youth.

The rejection by Germans, of fellow Germans displaced from the eastern part of the Reich, and made homeless by the war, continued unabated in the west, exacerbating his feelings of displacement. It was an ever present problem, as was the shortage of suitable family housing. With each addition to the Nikolaus Reitzug family it became more acute.

Not averse to risks, and always seeking to take care of his growing family, he applied to immigrate to Canada in 1953. A botched kidney surgery required a prolonged recuperation and ended that dream. But God opened another door, and in 1956 Nikolaus, Elisabeth, and five children immigrated to Fort Wayne, Indiana, where he pursued his career as an architect.

After painful starts in homes either too small or in a bad part of town, they settled in a new sub-division. In time this became a leafy suburb. It was home for Nikolaus the last 47 years of his life.

Years passed. Eight sons and daughters grew up, graduated, got married. 23 grandchildren and 26 great-grandchildren benefited from Nikolaus’s courageous decision to move to the US.

The laughing, happy young man from Mehlsack in East Prussia which no longer existed, was now 67 years old, had retired, had had his heart attack with a better outcome than Leo his father, and still missed his East Prussian home all this time. It was now possible to visit the country locked up for so long by that horrible war so many years ago. Klaus and Lisel, as Elisabeth was called, paid a long overdue visit to the longed for lands of long ago.

East Prussia, now deep in Poland, was still the lovely land, the lakes were still beautiful, and the important churches needing to be photographed, were still there. But without the people, the farms, the towns, and the old ways, it was not their Heimat. It now belonged to someone else.

After one last stroll through the romantic Walsch Tal, the scene of his romance all those years ago, it was time for Nikolaus to admit what he knew all along. The ever-so-faint dream of returning home to East Prussia was now firmly and finally extinguished.

And so the fourth Nikolaus Reitzug contented himself with visiting relatives, sons and daughters, watching grandchildren grow – and getting ready for that final home our hearts all long for.

In his last month of his life, at the age of 83 years, the demons of war that had haunted him for more than six decades, were put to rest. At peace, it wasn’t long before his soul rejoined his maker, I believe.

He would have been 100-years-old today.