Three mournful toots from the locomotive split the night air. It woke many of the weary passengers who had nodded off under the hypnotic clicking cadence of the train wheels. A series of long shrieks followed, metal grinding on metal as brakes were applied. Slowing down in shuddering jerks roused the last of the slumberers. With a convulsive final jolt, rippling from car to car as buffers bounced off each other, the train lurched to a stop.

Gustav had not slept. Until darkness made it impossible to see, he had pulled out his pocket watch every two minutes, popped the lid open, and checked the time. In between, he twirled and twisted the chain, wrung his hands, and wiped his brow with his handkerchief. When Marie put a hand on his leg to calm him, whispering reassuringly, “Na, ja, mein Liebchen,” he could only fold his arms across his chest and exhale deeply. Peering into the darkness, peace was elusive. The ghosts of his past were becoming unleashed.

It had been a difficult summer for 54-year-old Gustav. His health had begun failing after Elisabeth, his second oldest daughter had died in childbirth two months ago. The funeral in the dusty village of Jonkendorf (Jonkowo) was almost more than he could bear. He had named Elisabeth in honor of his mother. She was the only fond memory of his childhood. When he was six years-old she had died, also while giving birth. His daughter’s recent death under similar circumstances pricked the long-festering wound, baring many earlier losses.

Gustav’s mother Elisabeth was a young barmaid working for a 60-year-old widower, the village pub-owner in Braunswalde (Braswald). After becoming pregnant by him, she went back to the anonymity of her own village.There she gave birth to Gustav.

In Catholic East Prussia one person’s embarrassing secret became everyone else’s salacious gossip. The fact that she was Lutheran did not help. When he was almost a year old, Gustav’s parents did marry belatedly. But the damage had been done, the stigma and the whispers continued through childhood. Even children’s tongues can be cruel.

His mother’s death began a steep descent into loss and grief. His beloved maternal grandmother, the only grandparent he ever knew, passed away a year later. His father married again, this time to a woman 42 years his junior. But less than 4 years later he also died. Gustav, an 11 year-old boy, was orphaned. Overnight he had to become a man.

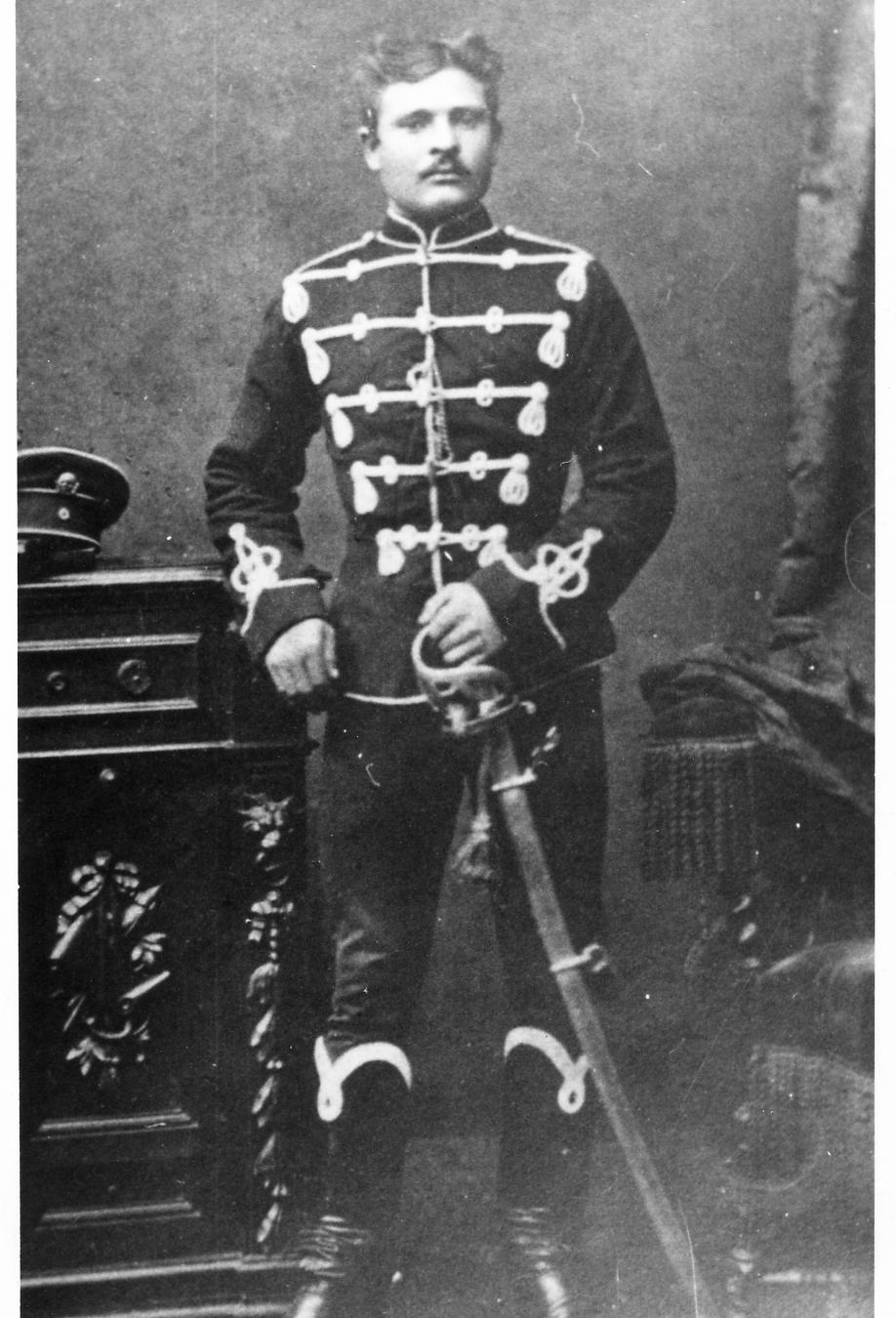

Once he was old enough, he joined the Prussian Army. Resplendent in a form-fitting tunic, rows of silver braids across his shoulders and chest, loops on his wrists and at the top of his leather jackboots, and a saber strapped to his hip, he looked the part of the Prussian military man. In the company of soldiers where the social niceties surrounding his birth did not matter so much, he flourished.

When he was ready to settle down his half-brother Julius, 19 years his senior, took him into his home and his wagon-making business in Allenstein (Olsztyn). When Marie came into Gustav’s life, he moved into a flat up the street at Warschauer Straße 25 (Niepodległości). The site is now occupied by a very upscale McDonalds. Six healthy children were born in that tiny apartment. Successful in his job, Gustav moved his family to more spacious accommodations at Liebstädter Straße 23 (Grunwaldzka). It was closer to Marie’s beloved Jakobi Kirche and the center of town. Life was good.

Marie understood him. Not judgmental, her own father had been raised by a single mother without the benefit of a man in the home, she was the stabilizing influence in his life. She persuaded him to attend St. Jakobi Kirche with her, and eventually he adopted Catholicism as his faith.

And then the turmoil of the summer of 1914 reached Allenstein.

Rumblings about Russian troop build-up south of the border had been the talk of July. Newspapers blared headlines pointing to imminent armed conflict. Burly 21-year-old Leo and feisty 19-year-old Felix had signed up to defend the Heimat. Anxiously Gustav hoped they would be OK. Seeing his brothers leave, 16-year old Nikolaus wanted to do his patriotic duty too. Named after Gustav’s father and the grandfather he never knew, young Klausche, as everyone called him, was the apple of his father’s eye. “If anything happened to Klausche, …,” He could not finish the thought. But it haunted him constantly.

Marie objected, but the boy had insisted. Gustav comforted his wife with the fact that he was 16 when he joined the Prussian Army. “But that was in peace time, before I knew you,” Marie had replied.

With the train stopped Gustav stood up and leaned out of the window to clear his head of torment. In the yellow glow of the only lamp on the station platform he could see a uniformed official in his short jacket with the tiny buttons, all undone in deference to the August heat which had persisted into the night. Hanging above his head a sign announced “Elbing.”

Free of the confines of sitting down, Gustav pulled out his cigarette lighter and his pocket watch. A burst of flame after several fumbling attempts and a snap of the watch lid showed him it was quarter to midnight. Before shoving the watch back into his pocket he attempted to give it a quick wind. It was already wound tight – from the last time.

“Almost twelve hours to travel 90 miles,” Gustav sighed.

Craning his neck he could see at least a dozen passenger cars with people hanging out of windows, some standing on the brakeman’s platform, all like him, anxious for information. The end of the train disappeared into the darkness beyond a curve in the track.

When they had boarded the train in Allenstein, Gustav was fortunate to get seats for himself, for Marie, and for 14-year-old Susie. The wooden benches were jammed full, people sat on suitcases and in the aisles; even the platforms at the front and back of each train car had people clinging to them.

Refugees fleeing Neidenburg (Nidzica) and Ortelsburg (Szczytno) had come through town speaking of horrific atrocities committed by Russian troops pouring across the border just 50 km south of Allenstein. “Die Russen kommen,” the Russian are coming, became the word on the street. It panicked Gustav.

The majority of Allenstein’s citizens had already left town, anticipating the worst. Most of the rest were now trying to leave. Railway officials added half a dozen empty coal cars and some cattle cars to accommodate the demand. Within minutes they were packed too. Fear for life outweighed care for possessions.

It was noon, August 25, 1914, when the long train left the Allenstein station.

***

After close to an hour on the smoothest motorway that EU money could build, Johann and I reached the outskirts of Allenstein. The battle of Tannenberg had been fought in this area exactly 104 years ago. There were no signs directing to memorials of that battle, or others fought in World War II in this area. A modern-day battle with earth movers, dump trucks, asphalt paving machines, and helmeted men in Hi-Vis vests was taking place ahead, and detoured us.

Rolling into town on the Aleja Warszawska, a broad boulevard, we passed the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn in a section of town called Kortowo, Kortau in German. An eclectic collection of buildings ranging from gracefully arched structures to Communist-era concrete slab blocks grace the campus. One ivy-covered brick building, a remnant of a different era, caught my eye.

In the 1880’s a sympathetically conceived and designed mental hospital had been built on this site, adjacent to one of Allenstein’s many lakes. At the time it was said to be the most advanced mental hospital in the eastern part of the Reich. In the early years they called it Provinziale Irrenanstalt, Provincial Insane Asylum. Stigma and political correctness caught up with it around 1900 and caused it to be repurposed and renamed, Provinziale Heil- und Pflegeanstalt, Provincial Healing and Care Institution.

Death records attest that Gustav Reitzug, my great-grandfather, died there in February 1915 after a prolonged illness.

***

Allenstein’s refugee train, after being stopped for two hours in Elbing, received news that the German Army under newly appointed General Feldmarschall Hindenburg had achieved remarkable victories in the field. It was deemed safe to return to Allenstein.

When the train of many cars rolled into Allenstein’s station the next afternoon, a surprise awaited the tired refugees. Russian soldiers had taken over the station and the town. It all seemed peaceful, but so frightening. The next two days would be the most harrowing days of their lives, even as not a single shot was fired and no violence took place.

More on the two-day peaceful invasion of Allenstein next time.

***

NB: Information was obtained from: My father’s ancestry archives,

“Ring of Steel – Germany and Austria in World War I” by Alexander Watson, 2014,

“Die Russen in Allenstein” by Paul Hirschberg 1916,

The David Rumsey Map Collection

Personal visit to Allenstein and a bit of story telling for readability

Thanks for your latest Blog, Henry! You make me curious about the next episode. How peaceful we experienced this country Poland and how much sorrow was associated with the same land for your parents and grandparents. It behooves us to strive for peace wherever we can. In our little family circle there was peace, probably because my daughter Ilsabe asked us not to talk politics. My former wife is leaning further to the right (AfD) than anyone else. A Blessed Advent for you and Ann! Johann

>

LikeLike

I agree, Johann. We must strive for peace in this polarized world. “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God.” Have a blessed Advent as well. Peace and Joy. Henry

LikeLike

You have captivated me with your writing, Henry. I can hardly wait until the next installment of your blog. I loved the photo of Gustav in his Prussian uniform–priceless. Until next time, may we all live in peace.

LikeLike

Thanks for reading and for your kind comments Sharon. More pictures coming next time.

LikeLike